- Thread starter

- #1

Rock Strongo

My mind spits with an enormous kickback.

"pete, you know youre not supposed to be in the hall"

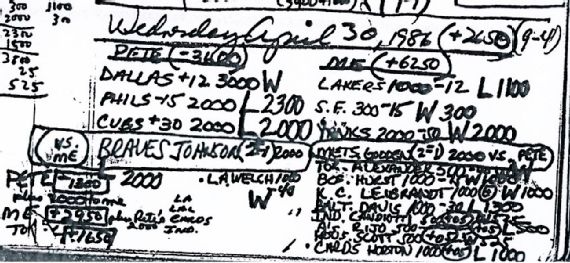

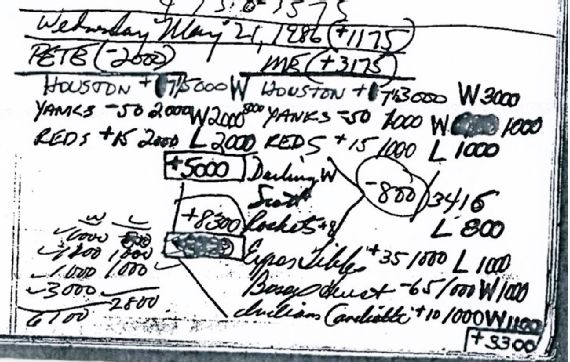

Notebook obtained by Outside the Lines shows Pete Rose bet on baseball as player in 1986

For 26 years, Pete Rose has kept to one story: He never bet on baseball while he was a player.

Yes, he admitted in 2004, after almost 15 years of denials, he had placed bets on baseball, but he insisted it was only as a manager.

Cincinnati Reds -- as he racked up the last hits of a record-smashing career in 1986. The documents go beyond the evidence presented in the 1989 Dowd report that led to Rose's banishment and provide the first written record that Rose bet while he was still on the field.

"This does it. This closes the door," said John Dowd, the former federal prosecutor who led MLB's investigation.

The documents are copies of pages from a notebook seized from the home of former Rose associate Michael Bertolini during a raid by the U.S. Postal Inspection Service in October 1989, nearly two months after Rose was declared permanently ineligible by Major League Baseball. Their authenticity has been verified by two people who took part in the raid, which was part of a mail fraud investigation and unrelated to gambling. For 26 years, the notebook has remained under court-ordered seal and is currently stored in the National Archives' New York office, where officials have declined requests to release it publicly.

Rose, through his lawyer, Raymond Genco, declined comment. Bertolini's lawyer, Nicholas De Feis, said his client is "not interested in speaking to anyone about these issues."

The documents obtained by Outside the Lines, which reflect betting records from March through July 1986, show no evidence that Rose, who was a player-manager in 1986, bet against his team. They provide a vivid snapshot of how extensive Rose's betting life was in 1986:

• In the time covered in the notebook, from March through July, Rose bet on at least one MLB team on 30 different days. It's impossible to count the exact number of times he bet on baseball games because not every day's entries are legible.

• But on 21 of the days it's clear he bet on baseball, he gambled on the Reds, including on games in which he played.

• Most bets, regardless of sport, were about $2,000. The largest single bet was $5,500 on the Boston Celtics, a bet he lost.

• Rose bet heavily on college and professional basketball, losing $15,400 on one day in March. That came during his worst week of the four-month span, when he lost $25,500.

Dowd said he wished he'd had the Bertolini notebook in 1989, but he didn't need it to justify Rose's banishment. Under MLB Rule 21, "Any player, umpire, or club or league official or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform shall be declared permanently ineligible."

But Rose's supporters have based part of their case for his reinstatement on his claim that he never bet while he was a player or against his team, saying that sins he committed as a manager shouldn't diminish what he did as a player.

"The rule says, if you bet, it doesn't say for or against. It's another device by Pete to try to excuse what he did," Dowd said. "But when he bet, he was gone. He placed his financial interest ahead of the Reds, period."

The timing for Rose, who played in 72 games in 1986, isn't great. In March of this year, he applied to new MLB commissioner Rob Manfred for reinstatement. Dowd recently met with MLB CIO and executive vice president of administration John McHale Jr., who is leading Manfred's review of Rose's reinstatement request, to walk McHale through his investigation. On Monday morning, MLB officials declined to comment about the notebook.

In April, Rose repeated his denial, this time on Michael Kay's ESPN New York 98.7 FM radio show, that he bet on baseball while he was a player. "Never bet as a player: That's a fact," he said.

Outside the Lines tracked down two of the postal inspectors who conducted the raid on Bertolini's home in 1989 and asked them to review the documents. Both agents, former supervisor Craig Barney and former inspector Mary Flynn, said the records were indeed copies of the notebook they seized.

When the case began, it didn't look particularly enticing, Barney said. The postal inspector's office in Brooklyn, New York, had received a complaint that a man in Staten Island had failed to return goods to paying customers that he was supposed to have autographed. The man's name was Michael Bertolini, and the business he ran out of his home was called Hit King Marketing Inc.

Bertolini pleaded guilty and received a federal prison sentence, Sports Illustrated, The New York Times, ESPN and other news organizations filed freedom of information requests with the U.S. Attorney's Office seeking access to the book. All were denied on the grounds that the notebook had been introduced as a grand jury exhibit and contained information "concerning third parties who were not of investigative interest."

Last year, Outside the Lines again applied unsuccessfully for access to the notebook but learned it had been transferred to the National Archives under a civil action titled "United States v. One Executive Tools Spiral Notebook." Two small boxes of other items confiscated in the postal raid on Bertolini's house went, too, including autographed baseballs and baseball cards.

In April, Outside the Lines examined the Bertolini memorabilia kept in the National Archives' New York office, but the betting book -- held apart from everything else -- was off-limits. The U.S. Attorney's Office internal memorandum from 2000 that requested the spiral notebook's transfer said Bertolini's closed file has "sufficient historical or other value to warrant its continued preservation by the United States Government." The memorandum listed among its attachments a copy of the notebook, but a copy of the memorandum provided by the National Archives had no attachments and had a section redacted.

"I wish I had been able to use it [the book] all those years he was denying he bet on baseball," said Flynn, the former postal inspector. "He's a liar."

To Dowd, one of the most compelling elements of the newly uncovered evidence is that it supports the charge that Rose was betting with mob-connected bookies through Bertolini. Dowd's investigation had established that Rose was hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt at the time he was banished from the game.

"Bertolini nails down the connection to organized crime on Long Island and New York. And that is a very powerful problem," Dowd said. "[Ohio bookie] Ron Peters is a golf pro, so he's got other occupations. But the boys in New York are about breaking arms and knees.

"The implications for baseball are terrible. [The mob] had a mortgage on Pete while he was a player and manager."

Notebook obtained by Outside the Lines shows Pete Rose bet on baseball as player in 1986

For 26 years, Pete Rose has kept to one story: He never bet on baseball while he was a player.

Yes, he admitted in 2004, after almost 15 years of denials, he had placed bets on baseball, but he insisted it was only as a manager.

Cincinnati Reds -- as he racked up the last hits of a record-smashing career in 1986. The documents go beyond the evidence presented in the 1989 Dowd report that led to Rose's banishment and provide the first written record that Rose bet while he was still on the field.

"This does it. This closes the door," said John Dowd, the former federal prosecutor who led MLB's investigation.

The documents are copies of pages from a notebook seized from the home of former Rose associate Michael Bertolini during a raid by the U.S. Postal Inspection Service in October 1989, nearly two months after Rose was declared permanently ineligible by Major League Baseball. Their authenticity has been verified by two people who took part in the raid, which was part of a mail fraud investigation and unrelated to gambling. For 26 years, the notebook has remained under court-ordered seal and is currently stored in the National Archives' New York office, where officials have declined requests to release it publicly.

Rose, through his lawyer, Raymond Genco, declined comment. Bertolini's lawyer, Nicholas De Feis, said his client is "not interested in speaking to anyone about these issues."

The documents obtained by Outside the Lines, which reflect betting records from March through July 1986, show no evidence that Rose, who was a player-manager in 1986, bet against his team. They provide a vivid snapshot of how extensive Rose's betting life was in 1986:

• In the time covered in the notebook, from March through July, Rose bet on at least one MLB team on 30 different days. It's impossible to count the exact number of times he bet on baseball games because not every day's entries are legible.

• But on 21 of the days it's clear he bet on baseball, he gambled on the Reds, including on games in which he played.

• Most bets, regardless of sport, were about $2,000. The largest single bet was $5,500 on the Boston Celtics, a bet he lost.

• Rose bet heavily on college and professional basketball, losing $15,400 on one day in March. That came during his worst week of the four-month span, when he lost $25,500.

Dowd said he wished he'd had the Bertolini notebook in 1989, but he didn't need it to justify Rose's banishment. Under MLB Rule 21, "Any player, umpire, or club or league official or employee, who shall bet any sum whatsoever upon any baseball game in connection with which the bettor has a duty to perform shall be declared permanently ineligible."

But Rose's supporters have based part of their case for his reinstatement on his claim that he never bet while he was a player or against his team, saying that sins he committed as a manager shouldn't diminish what he did as a player.

"The rule says, if you bet, it doesn't say for or against. It's another device by Pete to try to excuse what he did," Dowd said. "But when he bet, he was gone. He placed his financial interest ahead of the Reds, period."

The timing for Rose, who played in 72 games in 1986, isn't great. In March of this year, he applied to new MLB commissioner Rob Manfred for reinstatement. Dowd recently met with MLB CIO and executive vice president of administration John McHale Jr., who is leading Manfred's review of Rose's reinstatement request, to walk McHale through his investigation. On Monday morning, MLB officials declined to comment about the notebook.

In April, Rose repeated his denial, this time on Michael Kay's ESPN New York 98.7 FM radio show, that he bet on baseball while he was a player. "Never bet as a player: That's a fact," he said.

Outside the Lines tracked down two of the postal inspectors who conducted the raid on Bertolini's home in 1989 and asked them to review the documents. Both agents, former supervisor Craig Barney and former inspector Mary Flynn, said the records were indeed copies of the notebook they seized.

When the case began, it didn't look particularly enticing, Barney said. The postal inspector's office in Brooklyn, New York, had received a complaint that a man in Staten Island had failed to return goods to paying customers that he was supposed to have autographed. The man's name was Michael Bertolini, and the business he ran out of his home was called Hit King Marketing Inc.

Bertolini pleaded guilty and received a federal prison sentence, Sports Illustrated, The New York Times, ESPN and other news organizations filed freedom of information requests with the U.S. Attorney's Office seeking access to the book. All were denied on the grounds that the notebook had been introduced as a grand jury exhibit and contained information "concerning third parties who were not of investigative interest."

Last year, Outside the Lines again applied unsuccessfully for access to the notebook but learned it had been transferred to the National Archives under a civil action titled "United States v. One Executive Tools Spiral Notebook." Two small boxes of other items confiscated in the postal raid on Bertolini's house went, too, including autographed baseballs and baseball cards.

In April, Outside the Lines examined the Bertolini memorabilia kept in the National Archives' New York office, but the betting book -- held apart from everything else -- was off-limits. The U.S. Attorney's Office internal memorandum from 2000 that requested the spiral notebook's transfer said Bertolini's closed file has "sufficient historical or other value to warrant its continued preservation by the United States Government." The memorandum listed among its attachments a copy of the notebook, but a copy of the memorandum provided by the National Archives had no attachments and had a section redacted.

"I wish I had been able to use it [the book] all those years he was denying he bet on baseball," said Flynn, the former postal inspector. "He's a liar."

To Dowd, one of the most compelling elements of the newly uncovered evidence is that it supports the charge that Rose was betting with mob-connected bookies through Bertolini. Dowd's investigation had established that Rose was hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt at the time he was banished from the game.

"Bertolini nails down the connection to organized crime on Long Island and New York. And that is a very powerful problem," Dowd said. "[Ohio bookie] Ron Peters is a golf pro, so he's got other occupations. But the boys in New York are about breaking arms and knees.

"The implications for baseball are terrible. [The mob] had a mortgage on Pete while he was a player and manager."