- Thread starter

- #1

Psych3man

Active Member

From Woodstock to Toronto: The remarkable journey of Jake Muzzin

WOODSTOCK, Ont. – As the Greater Toronto Area disappears in your rearview mirror, Highway 401 toward Woodstock, Ont., flattens out.

WOODSTOCK, Ont. – As the Greater Toronto Area disappears in your rearview mirror, Highway 401 toward Woodstock, Ont., flattens out.

Only a few barns and fields of untouched snow dot the landscape. As the city of 40,000 draws nearer, there is a sign on the highway promoting the region: “Embrace your rural routes.”

Visitors are then greeted by a sign welcoming them to Woodstock, which calls itself “The Friendly City.” Fritzie’s, the town’s most venerable food stand advertises “potato bacon soup” in black plastic letters on a whiteboard out front.

To get to the Woodstock Community Complex in the south end of town, a number of roads divert around the Purina animal food manufacturing plant.

It was that manufacturing industry that brought Ed and Judy Muzzin to Woodstock. Judy worked at CAMI Automotive for 20 years and Ed worked at Hobart Brothers of Canada, manufacturing welding electrodes and tubular wire for the welding industry. Both were bought out of their respective companies during the last recession. Ed then moved on to the Labatt’s Brewery in London and Transfreight in Woodstock before working as a quality inspector at Armtec in Woodstock. The children of immigrants – Ed’s parents coming from Italy and Judy’s from the Netherlands – the couple shared a simple ethos that was instilled in them from their parents.

Be honest. Work hard. Be loyal. And show respect.

“What we wanted is a better chance for our children,” said Judy Muzzin.

That was how Jake Muzzin, the Maple Leafs defenceman, grew up. That is, hundreds of NHL games and millions of dollars later, still who he is.

“People work hard for what they have,” Muzzin said of Woodstock. “There’s nothing given. That’s how we were brought up. And that’s what’s led me to here.”

Muzzin may have grown up nearby, but he is new to the Leafs. As Toronto’s only major in-season addition, and with injuries to blueliners Jake Gardiner and Travis Dermott, few players have had to shoulder heavier expectations heading into the postseason.

Those who know Muzzin best believe he can handle that pressure – and not solely because of the Stanley Cup-winning experience he acquired with the Los Angeles Kings. No, to hear them tell it, it’s because of his small-town upbringing and a sense of perseverance, which has kept him grounded throughout an unlikely NHL career that never seemed like a sure thing.

Muzzin was five years old when he decided he wanted to play hockey. His best friend, Nate Geerlinks, was a year older and whatever he did, Muzzin did, too.

His parents were skeptical. With two other children – older sister Nina and younger sister Julia – they understood the financial burden of hockey. They wanted to be sure that if they invested in it, their son would as well.

They posed a challenge to Jake: Spend one winter in figure skating. Learn how to skate, first and foremost, and if he could survive through lessons that Nina was already taking, they’d register him in hockey the following winter.

Muzzin complained at first, but he was a natural on skates. Judy and Ed Muzzin felt they had instilled a sense of pride in working toward an end goal for their son.

It was only after Muzzin had to wear an alligator costume on skates in a Peter Pan production that they realized his desire to play hockey was serious.

“That,” said Judy, laughing, “just about killed him.”

The alligator costume was banished to the closet for good. Muzzin joined Geerlinks at the hockey rink the following winter.

In a unique arrangement, in order to keep Muzzin with his close friends, the Woodstock Minor Hockey Association granted him underage status and allowed him to always play a year up.

Toward the beginning of every season, Ed and Judy would approach Jake to ask him if he was still enjoying playing and if he wanted to continue.

“If he wasn’t all in, then we weren’t going to be in,” said Judy. “We asked him to give 100 percent. Because it was very expensive.”

Muzzin’s father took a strict line, explaining that if they were going to invest their time and money, he would ask Jake himself to invest just as much of himself in the game.

“Which was good,” Jake said. “It provided me with good morals and made me work hard for what I’ve got.”

Ed and Judy eventually stopped asking Jake if he wanted to continue. His passion was obvious. And so was his talent.

Woodstock had limited options for progression up the minor hockey ladder, so to play AAA, Muzzin had to make the 90-kilometre round trip to Brantford, Ont.

Zane Neily, then coach of the Brantford Minor Bantam AAA team, was initially impressed but their defence core was set. Muzzin had to show he could skate if he had any chance of making the team.

It didn’t take more than a few strides for the coaching staff to realize that wouldn’t be a problem.

“It was a shock,” said Neily, who praised Muzzin’s strength, reach and skating ability. “You don’t see a young guy come in and join your top two or three.”

Muzzin’s transition was seamless. He was young, but he was calm and composed. And strong.

“When you had Muzz on the ice, everyone played two feet taller,” Neily said. “There were skirmishes where Jake would step in there and things would get calm. Everyone would step away.”

Playing in Brantford meant Muzzin was often tasked with shutting down the stars of his age group across Southern Ontario: Logan Couture, Mike Hoffman and current Leafs teammate John Tavares.

Back in Woodstock, he filled his time by carving dents in his parent’s garage door with missed shots on a road hockey net. The town was free of distractions, to put it mildly.

“There’s not even a mall,” said Judy, laughing.

His family started to accept the fact hockey was more than a hobby. One day Jake returned home from school with a poem that he had written in English class.

The poem, which still hangs on the fridge in the Muzzin family home, is written from the perspective of a boy who loves hockey.

“I say I will make it to the NHL,” it reads. “I dream I will make it to the NHL. I will try my hardest.”

At 14, Muzzin was selected 11th overall in the 2005 OHL draft by the Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds.

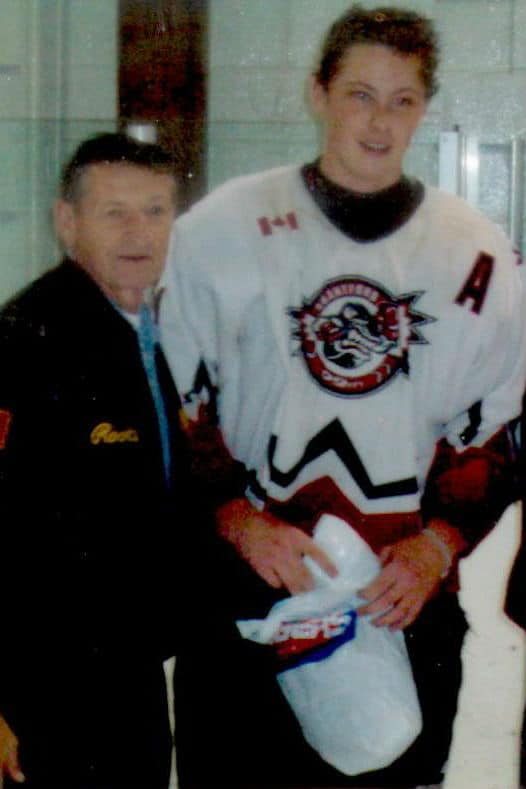

A young Jake Muzzin playing for Woodstock. (Courtesy of Judy Muzzin)

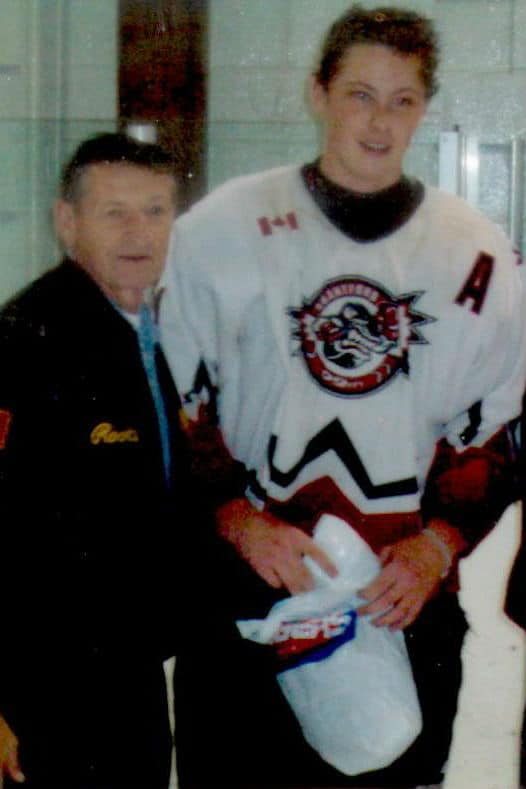

Jake meets Walter Gretzky. (Courtesy of Judy Muzzin)

Woodstock remembers. (Joshua Kloke/The Athletic)

To this day, the Muzzin family can’t pinpoint exactly when, or how, Jake’s back pain began to emerge. It could have been after a growth spurt, or it could have been a result of repeated body checks.

“Wear and tear,” Muzzin said, shrugging his shoulders.

But by 16, he had constant numbness and tingling in both of his legs. The pain meant he couldn’t sit for longer than 30 minutes at a time.

An MRI revealed a startling diagnosis: Muzzin had two herniated discs in his back.

The first plan of attack was to engage in rehab. But after a summer of three or four physiotherapy and massage therapy sessions a week, the pain wasn’t dissipating.

“A waste of time,” Muzzin said.

He began to wonder if he’d ever play hockey again. The once vocal and social teenager grew quiet and uncertain.

Ahead of the OHL season, Muzzin left Woodstock, unsure of his hockey future. That first seven-hour drive to Sault Ste. Marie was an uneasy one.

Hundreds of kilometres away from home, Muzzin didn’t play a single game. Instead, he continued rehab under the care of the Greyhounds doctors. Throughout the year, the organization’s prized prospect appeared at nearly 30 birthday parties and public events as a member of the Greyhounds, always keeping a lid on just how excruciating the pain could be.

By Christmas, Muzzin returned home with bad news. The rehab wasn’t working. Muzzin needed major surgery which could end his career. His NHL draft year was looming the following summer, and he’d lose one of the most crucial years of development for a young player.

He ultimately didn’t play a single game during the 2005-06 season.

The surgery left a jagged scar on his back a few inches long. After spending the summer healing, Muzzin moved back to Sault Ste. Marie to live with an unfamiliar billet family. He struggled to feel like he belonged with the Greyhounds.

“You’re not emotionally invested with the guys,” said Muzzin. “I was on the outside looking in.”

As a 17-year-old rookie in 2006-07, he played 37 games, establishing himself as a stay-at-home defenceman. The Pittsburgh Penguins took a flier on him in the fifth round of the 2007 NHL draft, 141st overall, but after multiple training camps, never offered Muzzin a contract.

“It made him a lot more motivated,” said Mike Quesnele, his teammate with the Greyhounds. “He tried to show these people what he could do.”

By Muzzin’s third OHL season, the Greyhounds were one of the youngest teams in the OHL. He saw a window of opportunity to add an offensive flair to his game.

Brock Beukeboom was a 16-year-old rookie that year and knew Muzzin had been drafted by the Penguins. He expected a boisterous voice who would bring tales of spending time on the ice with Sidney Crosby and Evgeni Malkin in training camps.

Instead, Beukeboom met an incredibly down-to-earth young man.

“If he saw something that was easily correctable, he’d be happy to point it out,” said Beukeboom. “He was never cocky. Always professional.”

That set Muzzin apart. First-round picks often enter major junior with too much pride.

“It’s a league full of egos,” said Nick Warriner, the Greyhounds assistant coach that year.

Unsigned by the Penguins, Muzzin’s only option was to return to the Greyhounds in 2009-10 for his overage year. The 2010 NHL draft class was heavy on OHL talent. A soon-to-be 21-year-old defenceman who had been passed over wasn’t exactly a high priority.

The Greyhounds named him captain. But Muzzin knew to follow through on the dream still hanging on his parents’ fridge, he needed to expand his game. He needed to be something new.

“He had to redefine his career a few times in his life,” said Judy Muzzin.

Muzzin broke out for 67 points in 64 games that season, leading the Greyhounds in scoring.

The Kings signed the free agent Muzzin to a three-year, entry-level contract. A few months later, Muzzin was awarded the Max Kaminsky Trophy as the OHL’s most outstanding defenceman.

It was only during that overage year that he finally played pain-free. Quesnele still wonders what could have been earlier in their OHL careers.

“Frig,” said Quesnele, “I wish he was healthy way back then.”

Only a few barns and fields of untouched snow dot the landscape. As the city of 40,000 draws nearer, there is a sign on the highway promoting the region: “Embrace your rural routes.”

Visitors are then greeted by a sign welcoming them to Woodstock, which calls itself “The Friendly City.” Fritzie’s, the town’s most venerable food stand advertises “potato bacon soup” in black plastic letters on a whiteboard out front.

To get to the Woodstock Community Complex in the south end of town, a number of roads divert around the Purina animal food manufacturing plant.

It was that manufacturing industry that brought Ed and Judy Muzzin to Woodstock. Judy worked at CAMI Automotive for 20 years and Ed worked at Hobart Brothers of Canada, manufacturing welding electrodes and tubular wire for the welding industry. Both were bought out of their respective companies during the last recession. Ed then moved on to the Labatt’s Brewery in London and Transfreight in Woodstock before working as a quality inspector at Armtec in Woodstock. The children of immigrants – Ed’s parents coming from Italy and Judy’s from the Netherlands – the couple shared a simple ethos that was instilled in them from their parents.

Be honest. Work hard. Be loyal. And show respect.

“What we wanted is a better chance for our children,” said Judy Muzzin.

That was how Jake Muzzin, the Maple Leafs defenceman, grew up. That is, hundreds of NHL games and millions of dollars later, still who he is.

“People work hard for what they have,” Muzzin said of Woodstock. “There’s nothing given. That’s how we were brought up. And that’s what’s led me to here.”

Muzzin may have grown up nearby, but he is new to the Leafs. As Toronto’s only major in-season addition, and with injuries to blueliners Jake Gardiner and Travis Dermott, few players have had to shoulder heavier expectations heading into the postseason.

Those who know Muzzin best believe he can handle that pressure – and not solely because of the Stanley Cup-winning experience he acquired with the Los Angeles Kings. No, to hear them tell it, it’s because of his small-town upbringing and a sense of perseverance, which has kept him grounded throughout an unlikely NHL career that never seemed like a sure thing.

Muzzin was five years old when he decided he wanted to play hockey. His best friend, Nate Geerlinks, was a year older and whatever he did, Muzzin did, too.

His parents were skeptical. With two other children – older sister Nina and younger sister Julia – they understood the financial burden of hockey. They wanted to be sure that if they invested in it, their son would as well.

They posed a challenge to Jake: Spend one winter in figure skating. Learn how to skate, first and foremost, and if he could survive through lessons that Nina was already taking, they’d register him in hockey the following winter.

Muzzin complained at first, but he was a natural on skates. Judy and Ed Muzzin felt they had instilled a sense of pride in working toward an end goal for their son.

It was only after Muzzin had to wear an alligator costume on skates in a Peter Pan production that they realized his desire to play hockey was serious.

“That,” said Judy, laughing, “just about killed him.”

The alligator costume was banished to the closet for good. Muzzin joined Geerlinks at the hockey rink the following winter.

In a unique arrangement, in order to keep Muzzin with his close friends, the Woodstock Minor Hockey Association granted him underage status and allowed him to always play a year up.

Toward the beginning of every season, Ed and Judy would approach Jake to ask him if he was still enjoying playing and if he wanted to continue.

“If he wasn’t all in, then we weren’t going to be in,” said Judy. “We asked him to give 100 percent. Because it was very expensive.”

Muzzin’s father took a strict line, explaining that if they were going to invest their time and money, he would ask Jake himself to invest just as much of himself in the game.

“Which was good,” Jake said. “It provided me with good morals and made me work hard for what I’ve got.”

Ed and Judy eventually stopped asking Jake if he wanted to continue. His passion was obvious. And so was his talent.

Woodstock had limited options for progression up the minor hockey ladder, so to play AAA, Muzzin had to make the 90-kilometre round trip to Brantford, Ont.

Zane Neily, then coach of the Brantford Minor Bantam AAA team, was initially impressed but their defence core was set. Muzzin had to show he could skate if he had any chance of making the team.

It didn’t take more than a few strides for the coaching staff to realize that wouldn’t be a problem.

“It was a shock,” said Neily, who praised Muzzin’s strength, reach and skating ability. “You don’t see a young guy come in and join your top two or three.”

Muzzin’s transition was seamless. He was young, but he was calm and composed. And strong.

“When you had Muzz on the ice, everyone played two feet taller,” Neily said. “There were skirmishes where Jake would step in there and things would get calm. Everyone would step away.”

Playing in Brantford meant Muzzin was often tasked with shutting down the stars of his age group across Southern Ontario: Logan Couture, Mike Hoffman and current Leafs teammate John Tavares.

Back in Woodstock, he filled his time by carving dents in his parent’s garage door with missed shots on a road hockey net. The town was free of distractions, to put it mildly.

“There’s not even a mall,” said Judy, laughing.

His family started to accept the fact hockey was more than a hobby. One day Jake returned home from school with a poem that he had written in English class.

The poem, which still hangs on the fridge in the Muzzin family home, is written from the perspective of a boy who loves hockey.

“I say I will make it to the NHL,” it reads. “I dream I will make it to the NHL. I will try my hardest.”

At 14, Muzzin was selected 11th overall in the 2005 OHL draft by the Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds.

A young Jake Muzzin playing for Woodstock. (Courtesy of Judy Muzzin)

Jake meets Walter Gretzky. (Courtesy of Judy Muzzin)

Woodstock remembers. (Joshua Kloke/The Athletic)

To this day, the Muzzin family can’t pinpoint exactly when, or how, Jake’s back pain began to emerge. It could have been after a growth spurt, or it could have been a result of repeated body checks.

“Wear and tear,” Muzzin said, shrugging his shoulders.

But by 16, he had constant numbness and tingling in both of his legs. The pain meant he couldn’t sit for longer than 30 minutes at a time.

An MRI revealed a startling diagnosis: Muzzin had two herniated discs in his back.

The first plan of attack was to engage in rehab. But after a summer of three or four physiotherapy and massage therapy sessions a week, the pain wasn’t dissipating.

“A waste of time,” Muzzin said.

He began to wonder if he’d ever play hockey again. The once vocal and social teenager grew quiet and uncertain.

Ahead of the OHL season, Muzzin left Woodstock, unsure of his hockey future. That first seven-hour drive to Sault Ste. Marie was an uneasy one.

Hundreds of kilometres away from home, Muzzin didn’t play a single game. Instead, he continued rehab under the care of the Greyhounds doctors. Throughout the year, the organization’s prized prospect appeared at nearly 30 birthday parties and public events as a member of the Greyhounds, always keeping a lid on just how excruciating the pain could be.

By Christmas, Muzzin returned home with bad news. The rehab wasn’t working. Muzzin needed major surgery which could end his career. His NHL draft year was looming the following summer, and he’d lose one of the most crucial years of development for a young player.

He ultimately didn’t play a single game during the 2005-06 season.

The surgery left a jagged scar on his back a few inches long. After spending the summer healing, Muzzin moved back to Sault Ste. Marie to live with an unfamiliar billet family. He struggled to feel like he belonged with the Greyhounds.

“You’re not emotionally invested with the guys,” said Muzzin. “I was on the outside looking in.”

As a 17-year-old rookie in 2006-07, he played 37 games, establishing himself as a stay-at-home defenceman. The Pittsburgh Penguins took a flier on him in the fifth round of the 2007 NHL draft, 141st overall, but after multiple training camps, never offered Muzzin a contract.

“It made him a lot more motivated,” said Mike Quesnele, his teammate with the Greyhounds. “He tried to show these people what he could do.”

By Muzzin’s third OHL season, the Greyhounds were one of the youngest teams in the OHL. He saw a window of opportunity to add an offensive flair to his game.

Brock Beukeboom was a 16-year-old rookie that year and knew Muzzin had been drafted by the Penguins. He expected a boisterous voice who would bring tales of spending time on the ice with Sidney Crosby and Evgeni Malkin in training camps.

Instead, Beukeboom met an incredibly down-to-earth young man.

“If he saw something that was easily correctable, he’d be happy to point it out,” said Beukeboom. “He was never cocky. Always professional.”

That set Muzzin apart. First-round picks often enter major junior with too much pride.

“It’s a league full of egos,” said Nick Warriner, the Greyhounds assistant coach that year.

Unsigned by the Penguins, Muzzin’s only option was to return to the Greyhounds in 2009-10 for his overage year. The 2010 NHL draft class was heavy on OHL talent. A soon-to-be 21-year-old defenceman who had been passed over wasn’t exactly a high priority.

The Greyhounds named him captain. But Muzzin knew to follow through on the dream still hanging on his parents’ fridge, he needed to expand his game. He needed to be something new.

“He had to redefine his career a few times in his life,” said Judy Muzzin.

Muzzin broke out for 67 points in 64 games that season, leading the Greyhounds in scoring.

The Kings signed the free agent Muzzin to a three-year, entry-level contract. A few months later, Muzzin was awarded the Max Kaminsky Trophy as the OHL’s most outstanding defenceman.

It was only during that overage year that he finally played pain-free. Quesnele still wonders what could have been earlier in their OHL careers.

“Frig,” said Quesnele, “I wish he was healthy way back then.”